- Home

- Tony Cavanaugh

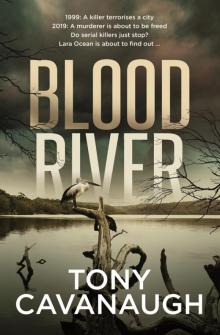

Blood River Page 16

Blood River Read online

Page 16

—

I COULDN’T HELP it. I started to giggle from the back seat of the police car, staring down the street to the rising pool of water on the cross street. I’d been good up until now, resigned to my fate but the realisation that the river had finally, after months of build-up pressure, burst its banks and that the city was going under, well, my controlled demeanour went under the surface and everything just seemed fucking ridiculous.

Roma Street Police HQ was about two hundred metres away from the river. Its foyer and ground floor would be under oily black flood water with maybe a few tree branches and some small dinghies; the force of the flow would have ripped through the main doors and windows.

‘Now what do we do?’ shouted the policewoman to her partner, who had no ready answer, just a dumb shrug. ‘And you,’ she said, turning around to face me. ‘Can you shut up with the giggling? It’s not helping!’

‘I’m not here to help you,’ I said as the giggling intensified. I stared at the black wave of river water in the city street and could not stop laughing at the absurdity of it all.

I was Alice in a dark and fucked-up wonderland, the night of Noah, the night of the dawn of the new next thousand years, the night of a massive joke which was a massive fear called Y2K. The last night of my freedom, the first day of my chains. Don’t mourn, Jen. Don’t weep, Jen. It’s all going to be okay, Jen, because there is nothing, nothing at all, that you can do to change the outcome Jen.

The policewoman glared at me. She was nothing like Lara. She was hard and her face seemed to dwell in sharp angles. She had short hair and looked, to me at least, as if she’d been beaten through childhood and was deciding to take out a bit of revenge on anything that came her way, that she could get away with.

‘Let me tell you something, Jen,’ she said angrily, ‘and I’ll tell it to you for free: you think you’re cleverer than us but you’re a smartarse. You belong to us now. Cops and the court. And if you keep up with the attitude, you’ll find yourself in a world of great and memorable pain.’ She turned back to the driver.

‘Fucking bitch. We’ll take her to the lock-up in the Valley. Radio through and tell the Homicide detectives to meet us there,’ she said.

He reversed up to the crest of the hill, turned right and sped up Ann Street. It was still dark. It was still raining. There were no cars on the roads and no people.

I didn’t listen to her warning. That, as it turned out, was a big mistake.

Dispatches

(III)

‘YOU’LL BE ELIGIBLE FOR PAROLE IN FIFTEEN YEARS’ TIME, okay. Life is not life,’ said Ian, my Queen’s Counsel, as I was led away by the bailiffs in the Supreme Court. As the floor was giving way to an impossible void of black and white, shifting worlds of startling nothing. As I tried to see if mum and dad were in the audience, but couldn’t see them. As Anthea was crying hysterically. As I was calculating: 18 + 15 = 33. As I was thinking, I’ll be thirty-three years old before I am eligible for parole, but the judge just gave me Life, which is, in my case, a twenty-year term: 18 + 20 = 38.

Originally, I was banking on a decade. 18 + 10 = 28. But then, while in remand, I got to hear about Tracey Wigginton, the Brisbane Lesbian Vampire Killer. She was convicted nine years ago, for thirteen. Everyone in remand, from the guards to the girls, looked at me weirdly: how come The Slayer has not heard of The Lesbian Vampire Killer? We thought you guys were related or something.

I thought I could hear people shouting that the judge had been too lenient, that he’d fallen for the She’s still a teenager and She’s never been in trouble before lines put forward by Ian. I thought I heard people calling for me to be tortured and hanged.

—

AFTER I WAS taken away that dark morning of January 1, 2000, formally arrested and sent before the magistrate in an emergency special session, mum and dad woke to discover I’d gone and Anthea told them I’d been driven off by the police. Dad hired a QC, which is the best you can get. Mum had been on dad to do it since he’d come home but Anthea told me she heard him say he didn’t want to spend the money, thousands of dollars a day, and anyway, he said, Anthea told me, he thought it would all blow over, it (me a suspect) being patently ridiculous.

Ian was on a pathway to becoming a judge on the High Court, so Anthea said, which is the top court in the country. He was very tall, old, wore a white three-piece suit like Tom Wolfe and spoke softly and he said, at the beginning of their first meeting: ‘My fee is ten thousand dollars a day. It’s a lot of money, so I need to be very up-front with you about this here and now. Expect to pay no less than half a million dollars for my team and I to fight for Jen’s acquittal.’

‘I’ll need to take out a loan against the house,’ replied dad, which is what Anthea told me. This was after I had asked her why they had moved into a small house in Bald Hills, north of the city.

‘They lost the house. They lost everything,’ she told me.

—

I WAS LED downstairs to a holding cell, a small concrete room with a narrow concrete bench on the back wall and an old-fashioned door with bars, like you see in the movies, and told to sit and wait. Which I did. I stared at the yellow-painted concrete wall that surrounded me. Why is it yellow? Who chose that colour? Where are they now? And there was, on the other side of the cell, a tiny hole and within this hole was a tiny insect trying to extricate itself and welcome itself into the cell of hell.

Life is not life.

—

AFTER A WHILE, the prison van arrived, backing into the underground car park area, which is connected to the yellow-painted cells, and I was escorted into the back of the van, also just like in the movies, and the back door was closed and locked and I sat on another bench as the roller-doors rose to let the van out into the city.

Did I tell you about the press inside the courtroom and outside the courtroom? Also, how people erupted in cheers when the guilty verdict came down, how their glee smothered the emotion of my sister, how the victims’ wives burst into tears and later one told the press how relieved they were that justice had been done but wasn’t it a shame that Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. She took my James away from me and our children; I hope the bitch stays behind bars until she’s too old to have children; I hope she dies behind bars. I hope she rots in prison and dies a horrible, long painful death.

I saw her say that on TV, in jail, and I knew she would carry those feelings towards me – wanting me to die painfully – for at least another forty or fifty years because Lynne was only in her mid-thirties. By the time her hate for me – and the hate of the other widows – dies, when they all die, I will be in my mid-fifties, maybe my sixties. And after they all die, if I am still alive, their hate will be carried on, towards me, by their children. Hate will stalk me for the rest of my life. For the rest of my life, there will be people who’ll want me to die in great pain and they will think about inflicting great pain upon me every day.

—

AS THE VAN left the confines of the court and swept up onto the street I could see and hear dozens of press people running alongside it, shouting at me and trying to snap a photo through the barred, grimy windows. Pop-pop-pop of the flashes as they held their cameras high above their heads, hoping to get me in frame.

—

BRISBANE CITY TO Wacol is about a thirty-minute drive.

Be thankful, Jen, that you’re not going to Boggo Road, which kept prisoners in the most awful, primitive, violent conditions, where men would be beaten and women raped and the place justly earned its reputation as one of the most Dickensian of all prisons in the country. I did a presentation on it for a Year 10 History class.

In comparison, my cell in Wacol is almost three-star; the decor is pale Greek-island blue with cream walls and a polished wooden desk and shelves. A highly polished metal toilet with no seat is bolted to the floor in the far corner. Above the toilet, on the wall, is a mirror. Made from metal, not glass. To its side is a window, framed with the same pale blue and a

lso not made of glass.

I have blue towels and a doona on my narrow single bed, which is up against the wall opposite the desk. Under the desk is a circular metal stool, also in the pale blue, bolted to the floor and it swings out so I can sit on it and write my dispatches. To me, to you, to whomever. Not mum and dad, that’s for sure. I’m writing to you now at four in the morning, before the doors will be opened and the routine will be adhered to. I am renting a flat-screen TV, from the prison, and I go to the library. I am not allowed internet.

Wacol is not a prison. It is a correctional centre. I, and my fellow-prisoner comrades, are here to be corrected.

The point of prison was, originally, quite simple: to punish the perpetrator for their crime, to make them as uncomfortable as possible by depriving them of freedom and sunlight, making them eat gruel and perform hard labour. Thus, rapes and beatings were part of the deal. Hence a place like Boggo Road. And then the point of prison became two-fold but with each fold being in a paradoxical battle with the other. Since sending prisoners on a convict ship to a dumping-ground land mass, Australia, there have been many so-called scientific ideas on how best to deal with prisoners, such as in Port Arthur, down in Tasmania, in the 1800s, where some inmates were made to wear cloth-masks over their heads so they couldn’t see another person and be in solitary twenty-three-seven; to the 1970s, when something new crept in: rehabilitation. While once you might have been on a chain gang like in that Paul Newman movie Cool Hand Luke, now you are starting to participate in cognitive-therapy sessions so that when you are released we did more than just fuck you with the best punishment we could summon. You are – and we did this to correct you – trained to become a better person, an adjusted human being, able to contribute to society. But in order to get there, and indeed to be paroled, you need to face something else.

Atonement.

Without atonement, there can be no parole. But, the thing is: I am innocent. So, how can I atone for crimes I did not commit? I can’t.

And I won’t.

Dispatches

(IV)

THE VANISHING

MUM AND DAD VANISHED. ANTHEA TOLD ME THEY’D MOVED to a small house in the almost-rural suburb of Bald Hills on the outskirts of the city, but I never saw them. They never visited. Anthea used to tell me they intended to. That rolled on for a few years then shuffled off-stage.

It’s okay.

Actually, it’s not, but I understand, I do. They were never the doting type. Mum worked full-time as a manager at a Honda dealership around the corner, down the hill, and dad was always flying around the world buying and selling art. Anthea and I got to appreciate that our birthdays were a stopover in their otherwise self-focussed world. It’s not like they were nasty or horrid or hit us or didn’t care for us. Dad once sent Anthea and me on a weekend trip to Sea World on the Gold Coast. A town car picked us up, dropped us off and there was a nice manager waiting for us in the foyer of the hotel with our tickets, all-inclusive for the week and any problems, to give her a call or just come down to the front desk. She told us we weren’t unique; other kids were sent alone because their parents were just so busy but loved them and wanted the best for them. Often kids from the UAE, she said. Last month they had a couple of wealthy kids from Malaysia. Nice kids, too. Parents flew them in on a private jet.

My parents were there but they weren’t. They always told us to call them if there was an issue and they would always apologise for being so busy but they loved us and after a while, you know what happens? You not only get blasé about it, but you build in so many mechanisms to cope, to be independent, you grow up really fast and you tend to not doorstop them for a problem, not wanting to bother them. Knowing you can deal with it yourself.

And in the wake of trauma, I get it. I do. It’s easier to ignore it.

—

I HAD A sort-of friend. Albano. He went to Churchie, the all-boys school. We met at one of those inter-school dances where teachers try not to look bored, and kids look awkward, chew gum and hover hands over pimples. We became sort-of friends and we started to meet in the mall on weekends and go to the movies. This was when I was fifteen. Just before the Goths and the Celts came to visit. Anyway, his mum died. She had a weak heart and it finally took her. Albano had known and he would occasionally mention it, but it was no big deal. Until she died and then, of course, it was a huge deal. He texted me. Mum just passed away. Texting had been around for a year or so and it was great because you didn’t have to speak to people. I didn’t text back. The next day he texted me again. Funeral is on Saturday. I didn’t text back. A week later, another text. Hey. Just wanted to see if you were okay. Miss you. I didn’t text him back. I couldn’t. It was trauma and all I could do was turn my back on it and pretend it didn’t exist.

For a moment, I thought I might have glimpsed Albano in the courtroom, in the crowd of people watching me. But I can’t be sure.

I have brought great shame on them. Mum. Dad. And, you know, kids shouldn’t bring shame on their parents. Kids are meant to bring pride to their parents. They were high-fliers and had money and a nice house and now their lives have been redefined in the most hideous way, by me. They had The Slayer living under their roof. With people asking: Did they know? And people answering: They must have, it’s inconceivable they didn’t. That’s what people would have said. I didn’t hear it. Nor did Anthea but you could hear it, bouncing from house to house across the city. How could they have not known? And, if they didn’t know, then what dreadful parents they must have been.

There’s no way out for them.

I know they love me.

Actually, I don’t.

They don’t. Not anymore. I killed that for them. How can you love a triple killer? Because if you do, you are doomed to an endless embrace of despair.

—

ANTHEA VISITS. SHE’S married now. She and Robbie (who has also never visited) bought a house in Ascot, not far from where we grew up, up on the hill looking out over the city and river. They have two little kids. She shows me photos. The girls, the munchkins. Jen is a little terror, she didn’t crawl; well, she did but only for about two months before she started to walk, and Anthea and Robbie are worried that she won’t develop her fine motor skills. They have done a lot of research on what to do about that because, you know, when she becomes a teenager it could have a psychological impact on her and so Robbie is now doing a kid football thing with her. Maxi is adorable and will break the boys’ hearts when she grows up.

Robbie works in finance and he was lucky to escape the GFC. I was vaguely aware of the Global Financial Crisis and sub-primes but I hate the news and, anyway, that sort of stuff means shit in prison. Same with climate change. Who cares? Let the world burn. You’re in fucking prison. I told her I was very happy Robbie still had a job.

Anthea and I, we never talk about why I am in jail. She knows I am innocent. Unlike mum and dad, who also know I am innocent but do nothing except stay inert and silent in the wake of the trauma, Anthea is supportive – she keeps me on life support.

I never really paid much attention to her. She was my little sister, so it was her duty to be out of my way, to not talk to me. I used to push her over a lot and she would go running to mum, or dad if he was home, and whinge and I’d get yelled at and blah blah blah. She’d creep into my room and steal things, and I’d use my make-up to paint her up as a scary clown with a big red nose and an extra big smile so it looked like her mouth went up to both sides of her face, up to her cheekbones. She would cry as I did this and I’d hit her like all big sisters hit their little sisters.

But, when she grew up a bit, she became nice to me, and she was so supportive when I was in the court. The only one, really. I have learned to rely on her. In my lonely little cell, she is all that I have.

—

BY THE WAY, how’s mum and dad?

I ask this every time she visits, and every time it’s met with a fake mention of them being okay, and after a moment I change the subject

back to her house and the renos and the kids and what Robbie’s fave meal is. (Pad Thai.) It’s easy to lapse into silence during these visits because, you know, I am a convicted killer and she is indulging me. I love it when she visits, but when we reach the water’s edge where mundane chatter turns to uncomfortable silence (Don’t leave, just stay a little longer) I say things like:

‘Did you know that Pad Thai was created as the Thai national dish after the King of Thailand declared a need for unity and identity, after the Second World War?’

‘You were always the smart one,’ she’ll say, but not in a nasty way. The older sister thing never entirely goes away, I guess.

Backtrack, Jen.

‘How are the butterflies?’

‘Yeah, good. Thanks. I better go.’

‘Okay. Thanks for visiting.’

‘No worries.’

‘Love to Robbie and the kids.’

‘I will.’

‘Say hi to mum and dad.’

‘Bye.’

‘Bye.’

‘Love you, big sis.’

‘Love you too.’

—

DOES SHE TELL her kids that their aunt is in prison for the gruesome murders of three men? Do her kids even know that I exist? Do they look into their mum’s photo albums from when she was a kid and ask: ‘Who’s that?’ And if they do, what would she say? Oh, that’s your aunty Jen. Why haven’t we met her?

Well, she’s The Slayer.

Sister Death

‘I TRIED TO CALL YOU.’

‘Oh sorry, I must have had the phone off.’

‘You were at the prison again, weren’t you.’

Blood River

Blood River