- Home

- Tony Cavanaugh

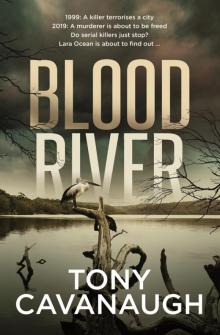

Blood River Page 9

Blood River Read online

Page 9

Serial killers may have been around since the dawn of time and perhaps the most famous, Jack the Ripper, made his splash in the last century but, really, it wasn’t until Hannibal Lecter graced the screen in 1991 that people, including cops, began to realise there was this whole new, beyond-creepy killer profile. The guy who won’t stop. The guy who does not fit the mould of angry, jealous boyfriend or schemer or the carrier of vengeance. They exist, for sure, but they’re as unusual as a UFO sighting.

And now I was working on a serial killer case.

I was scared.

Not of him, the killer. But of failure. The greater the profile of this case, and already we have media inquiries from all over the world, of detectives trying to solve the down-under exotic slasher who folds men’s heads back, the greater the potential for failure.

If we didn’t catch him, it wouldn’t just be the Commissioner who would make an example of us, throwing us to the wind to cover his own arse; it would be the press and the public, all angry at our impotence and inability to keep the city safe from an evil predator. Seven months into my dream job and I could already see the exit door. There were a lot of us working the case but Billy and I were leading it. First in, first out.

Billy also saw the threat. The oldest and most experienced cop of us all. As he often told me, he had been slugging crooks when Kristo, our Officer-In-Charge, was in nappies. He had also been giving evidence in Homicide trials when the Commissioner was falling off his tricycle. Billy had no intention of going down, at the end of his career, with the mark of failure.

‘You know what the likelihood is, don’t you, girlie? Of catching him,’ he said to me after Nils left the interview room, as we looked at one another, deflated. As much as either Miles or Nils could be our killer, and both men had the violence within them, we realised we were searching for a phantom. The normal rules of a murder investigation don’t apply, Billy told me, which I had figured out anyway.

‘He is meticulous, he has not left any prints, any firm sightings, any DNA. He has, maybe, left us a fucking flower and a Celtic symbol which is probably tattooed onto the backs of a few million young geezers with nought better to do with their time and money. He has also left us a grin, which he’s cut into their faces – fuck knows why, maybe it’s to laugh at us – and then ripped out one of their canine teeth. Probably one of them trophy things.’

And even if it is Nils or Miles, how do we connect all this? We are trying, using the usual routes, to identify whether they knew the victims, whether we have missed anything, whether there is a chance of us linking them to the moment of death, but we know it’s most likely futile.

Because the serial killer does not choose his victims like other killers. This is new. This is driven by psychology.

We know our guy likes to kill middle-aged and well-to-do men, which possibly means he has a problem with his mother. Or father. Perhaps was sexually abused. But maybe not.

‘We keep doing the Celt thing, we keep doing the sweep of North Stradbroke Island, we keep chipping away at Nils and Miles,’ Billy said to me. ‘And hope we, like our victims, get smashed by something random and unexpected because, girlie, to my way of thinking, these geezers don’t get caught by investigation, they just get unlucky.’

Skater Girl

‘HEY LARA, THERE’S A GIRL ON THE LINE AND SHE SAYS SHE might have information about your killer.’

Number twenty-eight thousand, two hundred and sixty-one. I’m being facetious but with our serial killer making news around the world, we were inundated with calls every minute or more. And, as Billy had said, this killer did not live in a vacuum, he did not visit us from another planet, he had a mother or a father or a wife or girlfriend or kids, and whoever that person was, they may be thinking he had been acting strangely or maybe they had seen a bloody knife or some bloody clothes. Within the deluge of crank calls there was, almost certainly, a sole lonely voice of someone who knew something.

Every lead had to be considered, regardless of knowing that a dead-end was almost always going to be the outcome.

Normally I tossed these calls to one of the lower ranks but there were only so many of those sorts of menial jobs you could toss to others before you became a prick. And I could never forget, I was twenty-six years old and seven months in.

I had been following up on a nagging instinct. One I had been trying to suppress. Was it possible that Damon had killed those three men? Surely, I told myself, he just had a creepy fascination with the case. Why not? It seemed as though the entire world had a creepy fascination with The Slayer, as he was now known, dubbed as such by the Courier Mail about two weeks ago.

We were almost three weeks in. Three weeks since James and then Brian and then Fabio, in a rapid spate, were killed. Three weeks of rain and storming, three weeks of fear, three weeks of a city increasingly feeling as though it was under siege.

I had been checking: Damon arrived in Brisbane two weeks before the first killing. He was living in Sunnybank, with his mother, in the old house next to my mum, waiting to hear back from the University of Queensland about a senior job as a lecturing professor. No criminal history. Which, to take a look at him, was not surprising. Nothing, from a scant check of the online newspaper Vancouver Sun, about killings like ours, when he was there, studying. I felt a bit guilty checking up on a friend.

‘Hello?’ I said, picking up the phone.

‘Hi. Am I talking to a police person?’ asked a scared-sounding young woman.

‘Yes, yes, you are. My name is Lara. Can you tell me why you’re calling?’

‘We’ve all been talking about it, and we think she’s the one.’

‘Sorry. Hang on; back up. Can you explain to me what you’re referring to?’

‘The killings. The guys with their throats cut. She’s a vampire.’

‘Okay … What’s your name?’

Silence. Then: ‘If you want me to give you my name I’m hanging up now.’

‘Okay. No problem. Just tell me what you know.’

‘She rides her skateboard through the Botanic Gardens at night and along the Kangaroo Point lookout. She worships Celtic gods and she’s covered in tatts.’

Which was when I stopped staring at my computer, sat up and paid attention. We had deliberately kept the Celtic stuff out of the press in order to explore the underground world without sending out any alarms.

We’d been told about a girl, a midnight skater, a shadow who zoomed around Kangaroo Point and the Botanic Gardens. She’d been seen on the nights of the killings. A dark blur of teenage freedom out late when she should have been home asleep ready for another school day.

We’d tried to find more on her, like an identity, as she might have seen something but:

Teenage girl on a skateboard? There are hundreds of them.

Nothing turned up, and so we moved on. She wasn’t a lead. Because she was a she and she was a teenager. Whoever she was. Both Billy and I eliminated her before we even knew her identity. She didn’t fit the profile. Teenage girl killer? Nonsense.

I put the call on speaker and gestured for Billy to listen. She sounded terrified.

‘Okay, look, sweetie; hope you don’t mind me calling you sweetie …’ I said in my best I-am-nice voice.

Billy nodded an affirmation to me as the girl replied, ‘That’s what mum calls me.’

‘My name is Lara. Okay?’

‘Hi Lara. Sorry, I don’t want to waste your time or anything …’

GET HER NUMBER AND HOME ADDRESS! NOW! Billy hurriedly scribbled onto a piece of paper and handed it to one of the analysts. Who ran back to his desk, passing the Christmas tree that one of the guys from another crew had brought in a week before. It was a real tree and the office smelt of pine needles. Cheap red baubles hung from its small branches.

‘We are all a bit scared, though. I’m really nervous,’ she said.

‘That’s okay, sweetie. No need to be nervous. You called her a vampire?’

‘That’s what

we call her.’

‘Why?’

‘She sucks blood. She’s evil.’

Which is when I nearly hung up on her, thinking I had been thrust into a teenage game or the fantasy of a kid who had been reading about Tracey Wigginton, the notorious Lesbian Vampire Killer from 1989. But Billy cautioned me in whispers across the desk: ‘Stay on the call, let’s listen to what she has to say.’

She kept talking to me.

‘I mean: hello, she’s not even eighteen and she’s covered in tatts; she’s a Goth; I think she has to be having sex with the tatt guy, and all of us, all of us, well, you know, they voted me to be the one to call you and I am not giving you my name, okay!’

‘Okay. No problem.’

Because, after about fifteen seconds, Billy and I had it. Her name.

One of the analysts had clocked her number and ran the ID.

I know who you are, where you live, what school you go to, what your parents do. I am even about to find out your choice of subjects.

And now, most importantly, as Billy leaned in and peered over my shoulder, at the computer screen, as we looked at your end-of-year school class photo, I know who you are talking about.

Second from left, front row.

Skater girl.

PART II

JEN

Mary wore three links of chain

Every link was Jesus’ name

Pharoah’s army got drownded

Oh Mary don’t you weep

One of these nights about twelve o’clock

This old world’s going to reel and rock

Pharoah’s army got drownded

Oh Mary don’t you weep

Moonage Daydream

OUR GIRL’S NAME, THE GIRL WHO RANG US THINKING SHE HAD been anonymous, was Donna Mex. We drove to her parents’ house in Ascot, up on the hill, not far from her school. Also close to where Lynne, Matt and Diane were suffering in their torment of grief. Donna’s house had a big view of the river and the city.

The rain had stopped. Which is not to say there was blue in the sky. The last blue sky was in October. Which is when it all began. Light rain at first. Nobody really noticed or cared. Hard drizzle and then, after a few days, four or five weeks ago, like an ominous threat of war, suddenly breaking with cannon-fire, rolls of hard thunder and masses of rain. Rain for days. Rain for weeks. Always, through this, a pause. A break. A tease.

But the rain always started again. Sometimes violently, without warning, sometimes a light drizzle which built to a torrent. Rain had become the new normal. Its absence was unnerving. We had become so used to constant rain, hard, light, heavy, living under a grey roof with its always-shifting shades of blizzard black and white, with temperatures soaring into the high twenties then into the mid-thirties, that when it momentarily did stop, we would look up to the sky and wonder if now, maybe, finally, now, a crevice would open and the blue beyond, which we were yearning for as if we had been living underwater and needed air, look up into the sky and hope. But it never came. The blue. The last blue was October twenty.

Maybe it wouldn’t come back. Maybe these were the end of days. Maybe the entire world would explode with the Y2K millennial bug.

We knocked. After a few moments the door was opened by Donna’s mum, who had the look of a sparrow. Petite, wispy blonde hair and dressed in a white caftan. She was on edge. We were all on edge. Non-stop rain and a never-ending grey roof does that to you.

‘Hello. My name is Detective Constable Lara Ocean, and this is Detective Inspector William Waterson and we would like to have a brief chat with Donna. There are no problems; she is not in any trouble, but she might be able to help us with some inquiries. Can we come in?’

—

BY NOW I had done a few face-to-face Homicide interviews with witnesses and possible killers and aggrieved lovers and parents of lost ones, and I had come to be sceptical about the meaning of body language. Sure, in some instances people look away and jiggle their leg and their hands might shake and their eyes might dart this way or that, which may indicate some guilt, an indication to Billy and me to hunker down and hammer them, but in my brief time in Homicide I have come to know that a reliance on a person’s body movements as you ask them tough questions, determining guilt, is nonsense.

Donna jiggled, tapped her feet on the floor and drummed her hands on her knees like she was Ringo Starr. She had the body language of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but she was just scared, out of her comfort zone in what had always been, until now, a place of security, a place where mum and dad might yell at her every now and then but, essentially, a sanctuary. Home had been turned upside down by the arrival of two cops. Tears were welling in her eyes and when she stopped doing the hands-drum-roll, she shrouded herself in a cocoon of arms wrapped tightly across her chest and rocked slowly backwards and forwards. She had dark brown hair, cut into a bob, like a 1920s fashionista, parted in the middle with upturned swishes on either side of her cheeks. She had wide green eyes and stared at us in what seemed to be constant bewilderment, rarely blinking. Her mouth stayed open in a perfectly formed O which gave her the look of being in perpetual surprise.

Her mum, whose presence was necessary because Donna was underage, looked away, out through the large open windows into the garden and beyond to the magnificent view of the river and the city from their perch on the other side of the hill. There was a dog out there. A Labrador, who was chasing its tail, and she followed its progression as if watching the final game at Wimbledon.

Billy sat back and gave Donna a smile, not an indulgent smile or a threatening smile, just the sort of smile you would look at and feel comfortable with, like he was a dad, and I did the talking, leaning in with:

‘Donna, you called us yesterday; it was me you spoke to.’

‘I didn’t. Why are you here?’

‘You did. Hey. Look, we’re the good ones. We come in peace, okay? There’s no problem, you’re not in any trouble, and if you want us to leave, we will.’

‘Yeah, I want you to go.’

‘Okay, no problem. Of course.’

We had rehearsed this. We were entering a new landscape. Of kids. Billy stood up, still smiling, as if to say: We are your friends, we respect your wishes.

I didn’t stand. I leaned across to Donna and lied. ‘My mum died when I was your age and I had to look after my little sister. I’m in my mid-twenties now and she’s sixteen. You’re sixteen, right?’

She nodded, eyes wide open and mouth in a perfect O.

‘So I look after her, my sis. She’s your age. I get it. Not only do I remember what it was like being sixteen, I’m living it every day. With her. So I get it. I get you just don’t want to have to talk to anyone who carries a badge or is like, you know, the authority. I know you don’t want to talk to me or the old guy – how about that after-shave, yeah?’

She smiled.

I had her. I was in.

‘Why don’t we, you and me huh, just have a walk in the back yard. It’s stopped raining. For like eight minutes …’

She smiled again.

‘… and if I ask you a question and you don’t want to answer it, you’re going to say … guess what?’

‘What?’

‘Fuck off, bitch.’

—

THE LABRADOR RAN around us, trying to engage us in a game known only to itself but every now and then would zoom off to chase a bird that had momentarily landed on the wet grass. We were walking slowly around one another, lazy and relaxed, circles, staring at the wall of trees on all sides of the garden, swishing away the occasional drip from an overhanging tree branch.

‘Donna, that phone call; why do you think Jen might be of interest to us?’

‘How do you know her name?’ she asked, shocked.

Fuck, Lara. Your L-Plate status is showing. Lucky Billy didn’t hear you mention Jen’s name. Don’t lead the person with your questions. You know that. You were taught that in the first week at the Academy; is it that hard to remember? Sill

y girl.

‘But that’s who you were calling about? Yeah? Jen White?’ I deflected.

‘She’s weird.’

‘How?’

‘She does all this Goth-shit stuff with knives and tattoos.’

‘What kind of stuff?’

‘She brought a knife to school. Actually, she did that, like, heaps of times; she has this wide, long-bladed knife she keeps in her backpack next to her Kafka and tell me if you think his shit isn’t weird …’

‘And what else? Why did you call us?’ I asked, wondering who Kafka was; it rang a distant bell, but unlike Donna, I didn’t go to a fancy school and I essentially left the world of education when I was fourteen.

‘Lately she’s been talking about sacrifice. Animals. People. She used to be normal, but now she skates in the middle of the night, through the city, along Kangaroo Point and she carries her flick-knife and laughs about how she might cut a guy and “bathe in his blood”, she calls it, like a vampire, and then she turns up at school the next morning with a – “Hey, how are you? Guess what I did last night?” And we say: “What did you do last night?” And she says: “I bathed in blood.” Like she’s acting out Countess Báthory.’

—

BY NOW DONNA had become emboldened and was on an unstoppable roll, like a dam had broken. I began to recoil from what was sounding like a teenage snakedance: a roller-skating schoolgirl killer, near-decapitating men in the middle of the night in the heart of Brisbane, carving a Celtic symbol onto their chest, channelling Elizabeth Báthory, a seventeenth-century noblewoman who also happened to be the most notorious female serial killer of all time (for a twining moment in my mid-teens, I had thought she was cool).

I knew that if and when we ever found our killer, he (now maybe she) would be a mind-twister of a person the likes of whom I could barely contemplate.

But. A teenage female serial killer? It seemed highly unlikely.

Blood River

Blood River